Paris Gun

| Paris Gun | |

|---|---|

The German Paris Gun, also known as William's Gun and "The Big Bertha" was the largest rail artillery gun of World War I. In 1918 the Paris Gun was able to shell Paris from 120 kilometres (75 mi) away. |

|

| Type | Super heavy field cannon |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| Used by | Imperial Germany |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Krupp |

| Manufacturer | Krupp |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 256 tons |

| Length | 28 m |

|

|

|

| Caliber | 210 mm, later 240 mm |

| Elevation | 55 degrees |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,600 m/s |

| Effective range | 130 km |

The Paris Gun (German: Paris-Geschütz) was a German long-range siege gun used to bombard Paris during World War I. It was in service from March-August 1918. When it was first employed, Parisians believed they'd been bombed by a new type of high-altitude zeppelin, as neither the sound of an airplane nor a gun could be heard. It was the largest piece of artillery used during the war by barrel length if not caliber, and is considered to be a supergun.

Also called the "Kaiser Wilhelm Geschütz" ("Emperor William Gun"), it is often confused with Big Bertha, the German howitzer used against the Liège forts in 1914; indeed, the French called it by this name, as well.[1] It's also confused with the smaller "Langer Max" (Long Max) cannons, from which it was derived; although the famous Krupp-family artillery makers produced all these guns, the resemblance ended there.

As a military weapon, the Paris Gun was not a great success: the payload was minuscule, the barrel required frequent replacement and its accuracy was only good enough for city-sized targets. However, the German objective was to build a psychological weapon to attack the morale of the Parisians, not to destroy the city itself.

Contents |

Description

The Paris Gun was a weapon like no other, but its capabilities are not known with certainty.[2] This is due to the weapon's apparent total destruction by the Germans in the face of the Allied offensive. Figures stated for the weapon's size, range, and performance vary widely depending on the source — not even the number of shells fired is certain.

The gun was capable of hurling a 94 kilogram (210 lb) shell to a range of 130 kilometers (81 miles) and a maximum altitude of 40 kilometers (25 miles) — the greatest height reached by a human-made projectile until the first successful V-2 flight test in October 1942.

At the start of its 170-second trajectory, each shell from the Paris Gun reached a speed of 1,600 meters per second (5,200 ft/s).

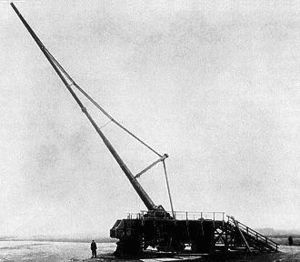

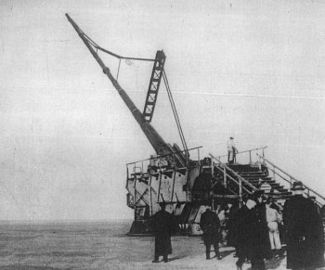

The gun weighed 256 tons and was mounted on a special rail-transportable carriage mounted on a prepared concrete emplacement with a turntable. It had a 28 meter (92 ft) long, 210 millimeter (8.3 in) caliber rifled barrel, with a 6 meter (20 ft) long smoothbore extension. This barrel was placed inside a 38 cm Langer Max barrel, which in turn was placed on the carriage. The gun's barrel was braced to counteract barrel droop due to its length and weight, and vibrations while firing.

Since it was based on a naval weapon, the gun was manned by a crew of 80 Imperial Navy sailors under the command of an admiral. It was surrounded by several batteries of standard army artillery to create a "noise-screen" chorus around the big gun so that it could not be located by French and British spotters.

The projectile reached so high that it was the first human-made object to reach the stratosphere. This virtually eliminated drag from air resistance, allowing the shell to achieve a range of over 130 kilometres (81 mi). The Paris Gun was the largest gun built at the time, but it was surpassed in all respects but range in World War II by the Schwerer Gustav. The unfinished V-3 cannon and Iraqi super gun would have been bigger.

Projectiles

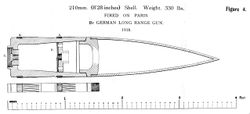

The Paris Gun shells were propelled at such a high velocity that each successive shot wore away a considerable amount of steel from the rifled bore. Each shell was sequentially numbered according to its increasing diameter, and had to be fired in numeric order, lest the projectile lodge in the bore, and the gun explode. Also, when the shell was rammed into the gun, the chamber was precisely measured to determine the difference in its length: a few inches off would cause a great variance in the velocity, and with it, the range. Then, with the variance determined, the additional quantity of propellant was calculated, and its measure taken from a special car and added to the regular charge. After 65 rounds had been fired, each of progressively larger caliber to allow for wear, the barrel was sent back to Krupp and rebored to a caliber of 240 mm (9.4 in) with a new set of shells.

The body of the shell was composed of massively thick steel, containing around 15 kg (33 lb) of explosive[3] in two compartments. The small amount of explosive – 15% of the weight of the shell – meant that the effect of its shellburst was considered small for the shell's size[3]. The wall separating the compartments strengthened the shell and supported the explosive charge under the massive acceleration of firing. One of the shell's two fuses was mounted in the wall, with the other in the base of the shell.

The shell's nose was fitted with a streamlined, lightweight, ballistic cap – a highly unusual feature for the time – and the side had grooves that engaged with the rifling of the gun barrel, spinning the shell as it was fired so its flight was stable. Two copper driving bands provided a gas-tight seal against the gun barrel during firing.[3]

Use in World War I

The gun was fired from the forest of Coucy and the first shell landed at 7:18 a.m. on March 21, 1918. Only when sufficient shell fragments had been collected was it realized that the explosion had come from a shell. It did not take long to discover the gun's location. Within a few hours of the start of the bombardment it was located by French aviator Didier Daurat.

The Paris gun was used to shell Paris at a range of 120 km (75 miles). The distance was so far that the Coriolis effect — the rotation of the Earth — was substantial enough to affect trajectory calculations. The gun was fired at an azimuth of 232 degrees (west-southwest) from Crépy-en Laon, which was at a latitude of 49.5 degrees North. The gunners had to account for the fact that the projectiles landed to the right of where they would have hit if there were no Coriolis effect.

In total, about 320 to 367 shells were fired, at a maximum rate of around 20 per day. The shells killed 250 people and wounded 620, and caused considerable damage to property. The worst incident was on 29 March 1918, when a single shell hit the roof of the St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church, collapsing the entire roof on to the congregation then hearing the Good Friday service. A total of 88 people were killed and 68 were wounded.

The gun was taken back to Germany in August 1918 as Allied advances threatened its security. The gun was never captured by the Allies. It is believed that near the end of the war it was completely destroyed by the Germans. One spare mounting was captured by American troops near Château-Thierry, but the gun was never found; the construction plans seem to have been destroyed as well.

The Paris Gun holds a significant place in the history of astronautics. In the 1930s, the German Army became interested in rockets for long range artillery as a replacement for the Paris Gun—which was specifically banned under the Versailles Treaty.

In popular culture

A parody of the Paris Gun appears in the Charlie Chaplin movie The Great Dictator. Firing at the Cathedral of Notre Dame the Germans succeed in blowing up a small outhouse.

See also

- Krupp K5 ("Anzio Annie")

- 21 cm K 12 (E)

References

Notes

- ↑ For an instance of war-time naming of this gun as "Big Bertha", see Paris again Shelled by Long-Range Gun The New York Times, August 6, 1918, page 3 online abstract

- ↑ With the discovery (in the 1980s) and publication (in the Bull and Murphy book) of a long note on the gun written shortly before his death in 1926 by Dr. Fritz Rausenberger, who was in charge of its development at Fried. Krupp, we are now fairly certain of the details of its design and capabilities.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Major J. Maitland-Addison (July-September 1918). "The Long Range Guns". The Field Artillery Journal (3). http://sill-www.army.mil/FAMAG/1918/JUL_SEP_1918/JUL_SEP_1918_PAGES_321_341.pdf.

Further reading

- Henry W. Miller, The Paris Gun: The Bombardment of Paris by the German Long Range Guns and the Great German Offensive of 1918, Jonathan Cape, Harrison Smith, New York, 1930

- Gerald V. Bull, Charles H. Murphy, Paris Kanonen: The Paris Guns (Wilhelmgeschutze) and Project HARP, E. S. Mittler, Herford, 1988

- Ian V. Hogg, The Guns 1914 -18, Ballantine Books, New York, 1971

External links

- Harry W Miller, United States Army Ordnance Dept, Appendix I : The German Long Range Gun. In Railway Artillery: A Report on the Characteristics, Scope of Utility, Etc., of Railway Artillery, Volume I. Washington, Government Print Office, 1921

- The Paris Gun in the First World War.com Encyclopedia

- Paris Gun at S. Berliner, III's ORDNANCE

- Une page sur le canon de Paris

|

|||||||||||||||||